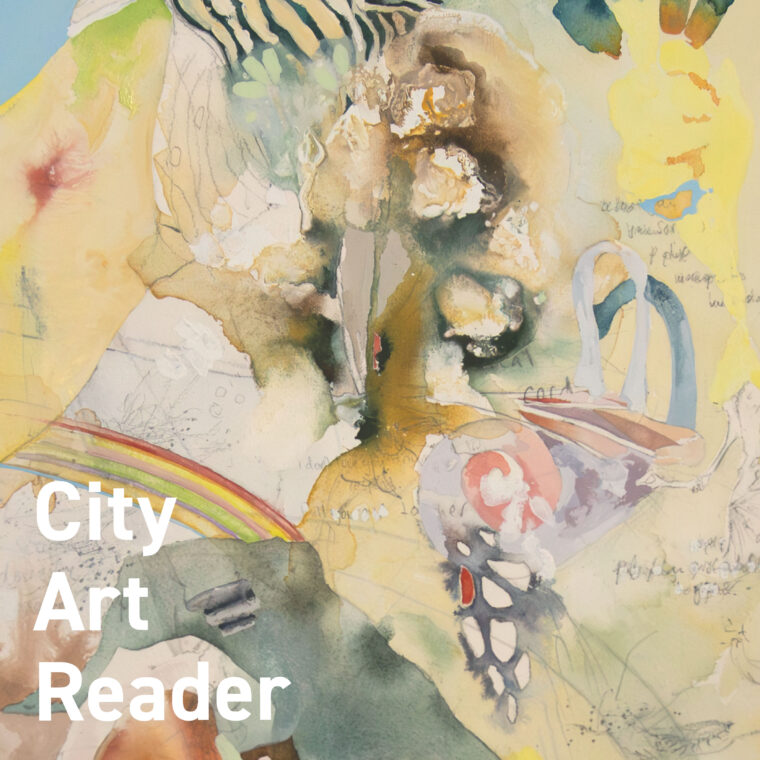

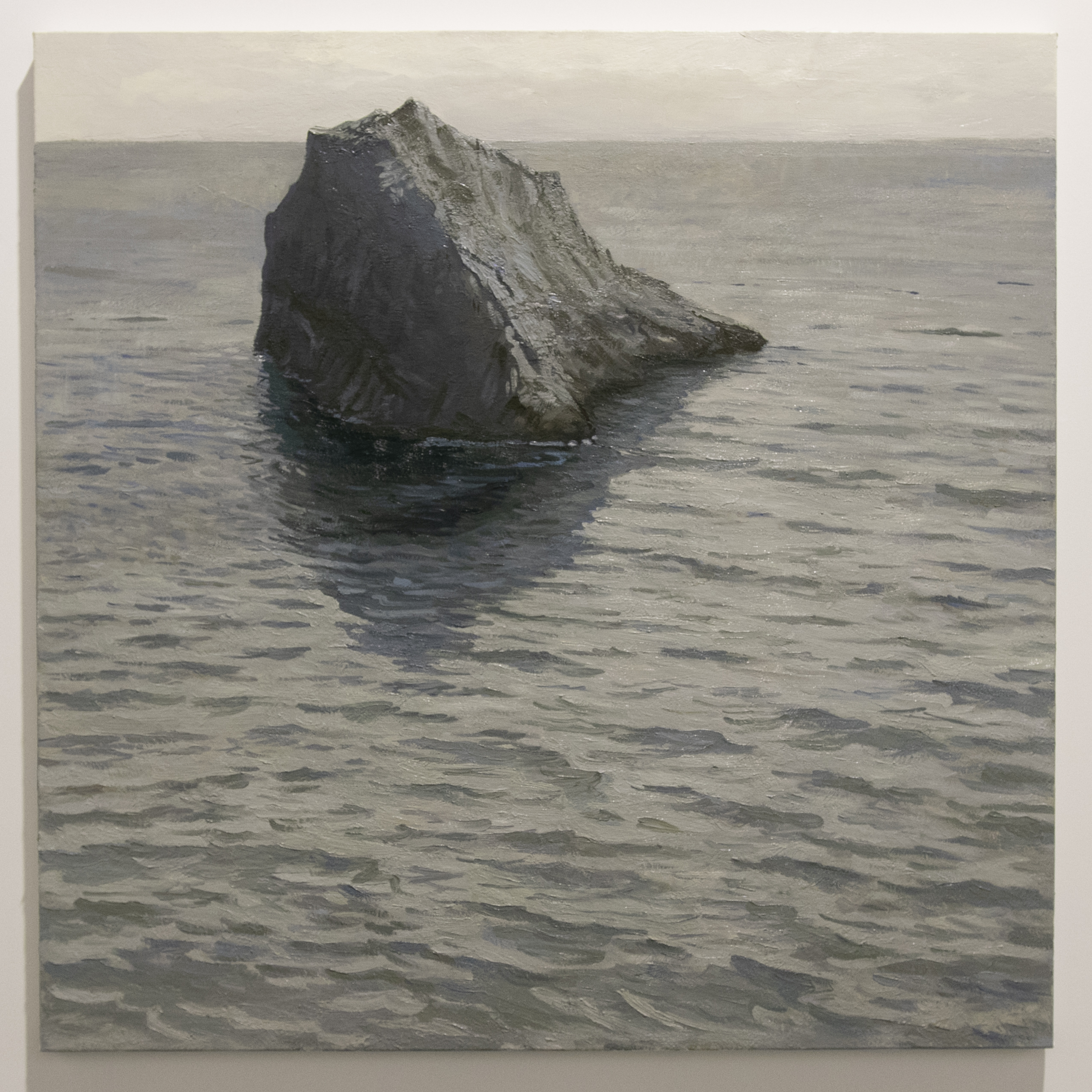

In 無常 (mujō) Te Waipounamu South Island based painter Richard Elderton chases the notions of impermanence and transience. The body of work reflects Elderton’s own shifting perspective, drawing abstract connections between structures, isolating details and omitting or inferring narrative significance. Ahead of the exhibition, he discussed his works with City Art Depot gallery manager Cameron Ralston. 無常 (mujō) opens 5.30pm Tuesday 18 July and runs through to 7 August.

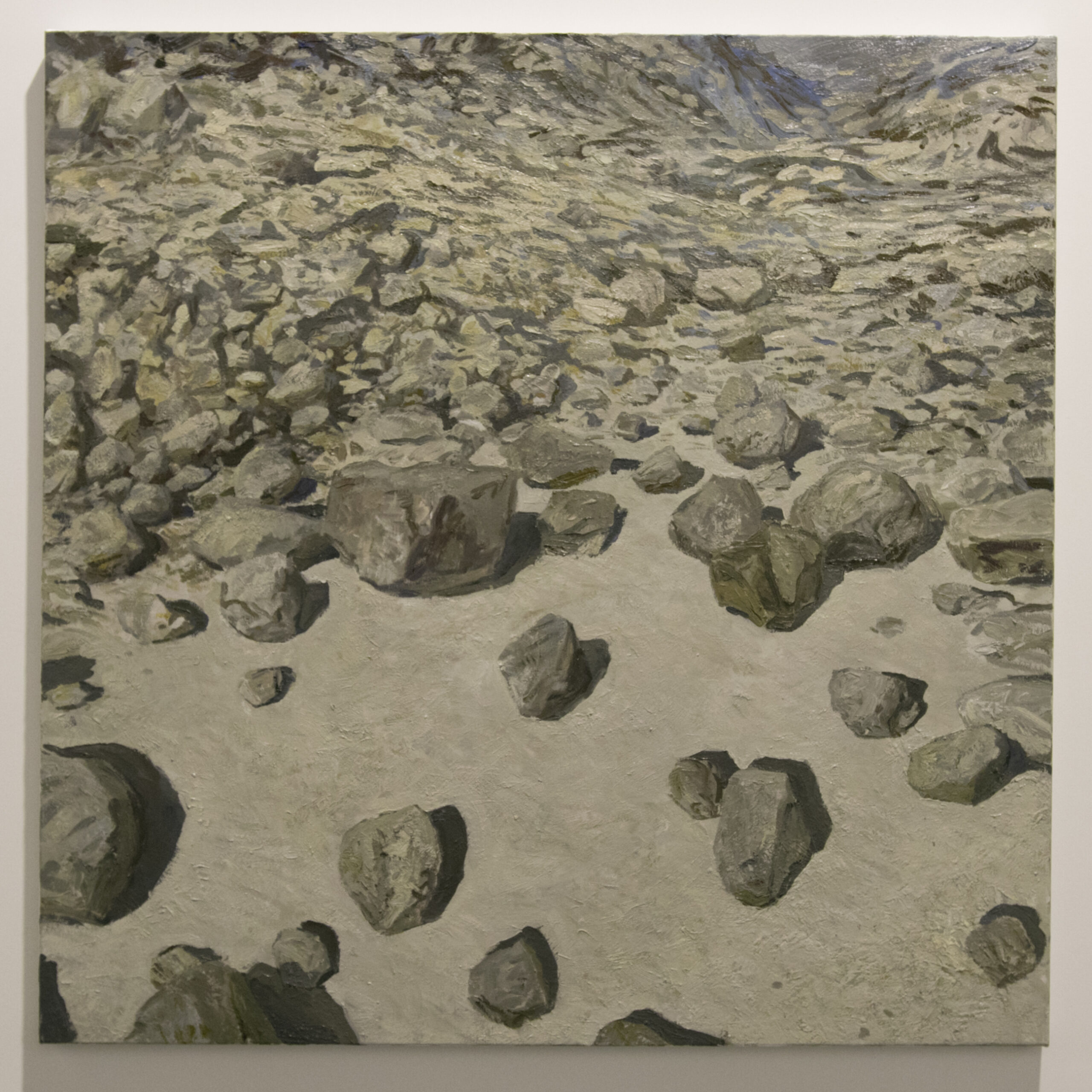

波の呼吸—Stone and Undulation, oil on stretched canvas, 1220x1220mm, 2023

Cameron Ralston: What does the idea of mujō mean? And what does it mean for you?

Richard Elderton: Mujō means constantly changing, nothing is constant, nothing remains. I used it as a reference to the Buddhist four-letter proverb 諸行無常 (shogyō-mujō), which refers to the impermanence of all. It’s an old concept that appears again and again in Japanese literature and throughout the historical aesthetics of Japanese culture. For me, in the process of making the works, I was chasing after this feeling and when I finished all the works and was looking at them, I got this feeling of constant shifting. It just seemed to fit.

Do the works have a spiritual element?

I don’t know if they embody, or encapsulate, anything spiritual. But I was definitely wrestling with spiritual significance. I was reading literature around concepts of religion and the scientific revolution. So I think they are based around the question of spiritual value.

How does that idea of impermanence fit with the works?

It’s very hard to articulate, because I didn’t sit down and do research and come up with a theoretical starting point. I was chasing after the feeling. I was looking for that fleeting feeling, that time is slipping through our fingers. There are no figures in the works but I think that when you do a painting it’s necessarily from the viewpoint of people. So, it raises the questions: where is the perspective? And where are the people? Where do they stand in relation to what is being presented?

You have three different elements which you’ve investigated: rocks, fabrics and pendulums. Are those subjects that you felt represented these ideas of impermanence? How do they fit together with each other?

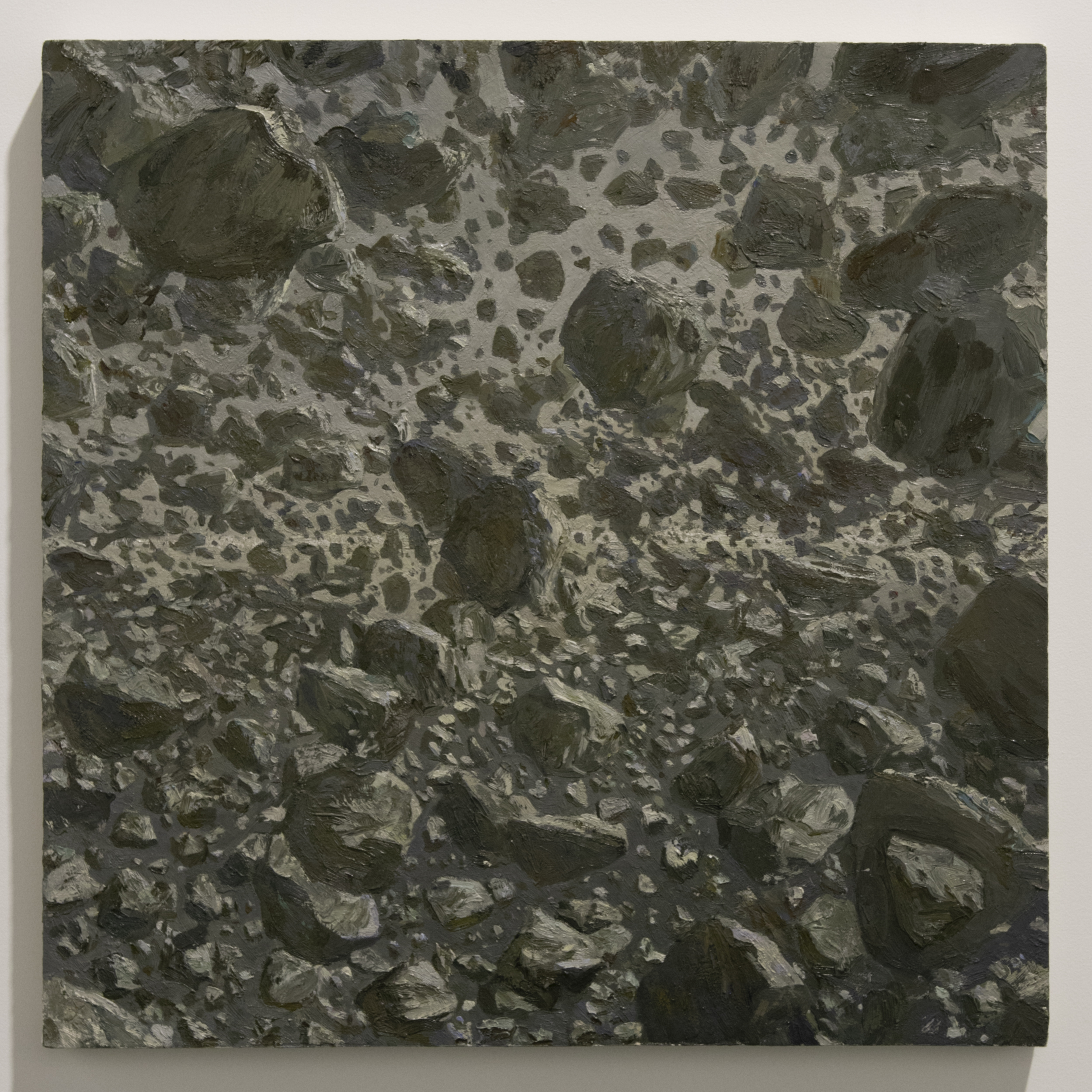

They all have this temporal aspect to it. One of the things that I consciously looked for in my subjects was the idea that in a way they’re an abstraction. Like you can imagine a piece of fabric, but there’s no particular formula to the way a piece of fabric ought to look. It’s not like a portrait where you have two eyes and a nose in the middle, it depends on the lighting and angles, and the physics that apply to the material, so much so that it becomes this abstraction. The same goes for the reflective spheres and the rocks. Everyone knows what a rock looks like, but there’s no defining feature of a rock, so it has this resonance. It’s a form of realism but simultaneously abstract.

流浪—Whims of the Wind, oil on stretched canvas, 380x510mm, 2023

So, it’s all imagined scenes? In the previous landscape paintings you exhibited with us you said they were a mix between Japanese and New Zealand landscapes. Is the same true here?

Yeah, imagined for the most part. I have to stick with what resonates with me personally. So, there’s my own cultural upbringing and what appeals to my sensibility. Ultimately, I’m trying to look for something that resonates with a universal human condition as opposed to something that is too specific to me or any one particular culture.

Temporality, impermanence, transience, these are universal ideas. It’s interesting looking at how you’ve used light and shadows in the works – in some of them it feels difficult to find the point of light or perspective within them. Was that quite a deliberate choice?

Yeah, the perspective thing was conscious. As I mentioned before, I read the human condition into basically every painting I see, products made by humans for unknown reasons, and there’s a mystery to that. There’s an enjoyment to the unravelling of that. So, in turn, there’s a tension to displacing the human perspective or omitting that deliberately from the subject. You want to read into the painting and find exactly where it is, but you can’t. That play was something I was looking to achieve in the works. I’ve always loved the illusion of light in paintings, directional light, and the different effects of light. I guess going back to the selection of motifs, there was an element of choosing subjects that responded differently to light. With rocks you have a solid matte opaque object onto which light falls and casts a shadow. Whereas if you polish it and it becomes a reflective surface it becomes more unpredictable. Then light passes through fabric. So, they’re responding in different ways. I think it plays into that reading of the human condition and perspective of it. Different manifestations of the way light responds to different materials can conjure different emotional responses.

A lot of your works have a feeling of calm or contemplation, especially in the earthy muted colour palette you’ve chosen for these paintings. Does that fit into the emotions you’re talking about?

A friend told me that there’s a sense of restraint, which I think is exactly what I was feeling. I usually like to use colours and include strong accents but I was quite consciously trying to restrain myself with this body of work. Keep it on this line of near monochrome, but not quite. At first there’s a matter-of-factness to that restraint. But I think over time when you look at it and start identifying some of those colours or the way the saturation has been literally pushed back, you get this feeling that there’s something underneath it.

How do you mean underneath it? Literally?

I’m deliberately omitting things and deliberately pushing certain colours back. I start off with quite saturated bright colours and then gradually push it back, working wet into wet, so you still get streaks of colours but I hope you can see they have been worked over to achieve that near monochrome.

I did notice that in getting up close to some of the paintings, thinking particularly of ‘漂流群—Float Rocks’ around the border of the rocks, streaks of a more vibrant yellow become noticeable. It is enjoyable with your works to spend time observing them at different distances and noticing the nuances in the way you’ve applied the paint.

That’s really important to me. My favourite paintings are the ones that can make a thousand different readings of it just by standing in different places and looking from angles. I try to bring that into my own works as much as possible.

漂流群—Float Rocks, oil on stretched canvas, 1220x1220mm, 2023

Did you look at other Japanese concepts around art?

In terms of the process, I didn’t necessarily start with a theoretical standpoint, but rather an emotional abstraction. In terms of the process of developing the work, I load myself up with stuff. I look at films, paintings, books, poetry, have conversations. Anything I could get my hands on to load up and then somehow synthesise all that.

Is that consuming anything and everything? Or are you directed in what you’re looking at?

Anything that intrigued me. I did revisit a lot of what’s considered Japanese art. It’s a whole topic of its own. To my mind ‘art’ has its historical roots in the west. Japan, you can say it has art, but it has its own thing. I’ve always had this struggle with resolving that tension. I was looking at a lot of Japanese works and, on my way here, I was thinking about Ryōanji, this famous temple garden, which has all these rocks. It’s a dry garden so there’s a plane of white sand, like clouds or a body of water, and then you have an arrangement of larger rocks. You sit on the balcony and observe the rocks, but it’s designed so you can never see all fifteen rocks from any particular angle from the balcony. I like that idea of never getting the full picture, so you always have to add your imagination to it. That’s how I tried to bring these concepts together. So as a whole you can begin to attribute narratives and read in certain concepts, but you never get a full picture of the whole body of work. You get maybe 80% and the other 20% doesn’t make sense in that context. But if you look at it another way you get a different 80%.

Do you think that what’s obscured is the intrigue?

Yeah. I like art that I can’t understand.

Is that reflected in what you were reading and watching? Do you have any examples?

I think so. One of my recent and biggest influences was the works of Conrad Hall, an American cinematographer, who did movies like Road to Perdition and Searching for Bobby Fischer. I watched a whole bunch of his films. He originally started out in black and white, shooting with high contrast and all these shadows but the way he brought textures and the framing of each scene into it intrigued me. They all play into the story. For a cinematographer I think the biggest priority is how does the visual storytelling contribute to the overall storytelling. They’re abstractions. You get these moments like drops of water on a spinning bicycle wheel or the texture of crystals with light travelling through them. Somehow those little abstractions play into the story. You can only understand so much of it, but you can feel it. It was fun going through a bunch of his films and playing with that idea.

運츱帯—Eye in the Asteroid Belt, oil on stretched canvas, 595x595mm, 2023

It’s interesting how many painters these days are influenced heavily by film.

I look at a lot of paintings as well. Hundreds and hundreds. One of my recent influences is a Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin. He’s most well-known for his Isle of the Dead series. But it’s kinda cute…

…Cute?

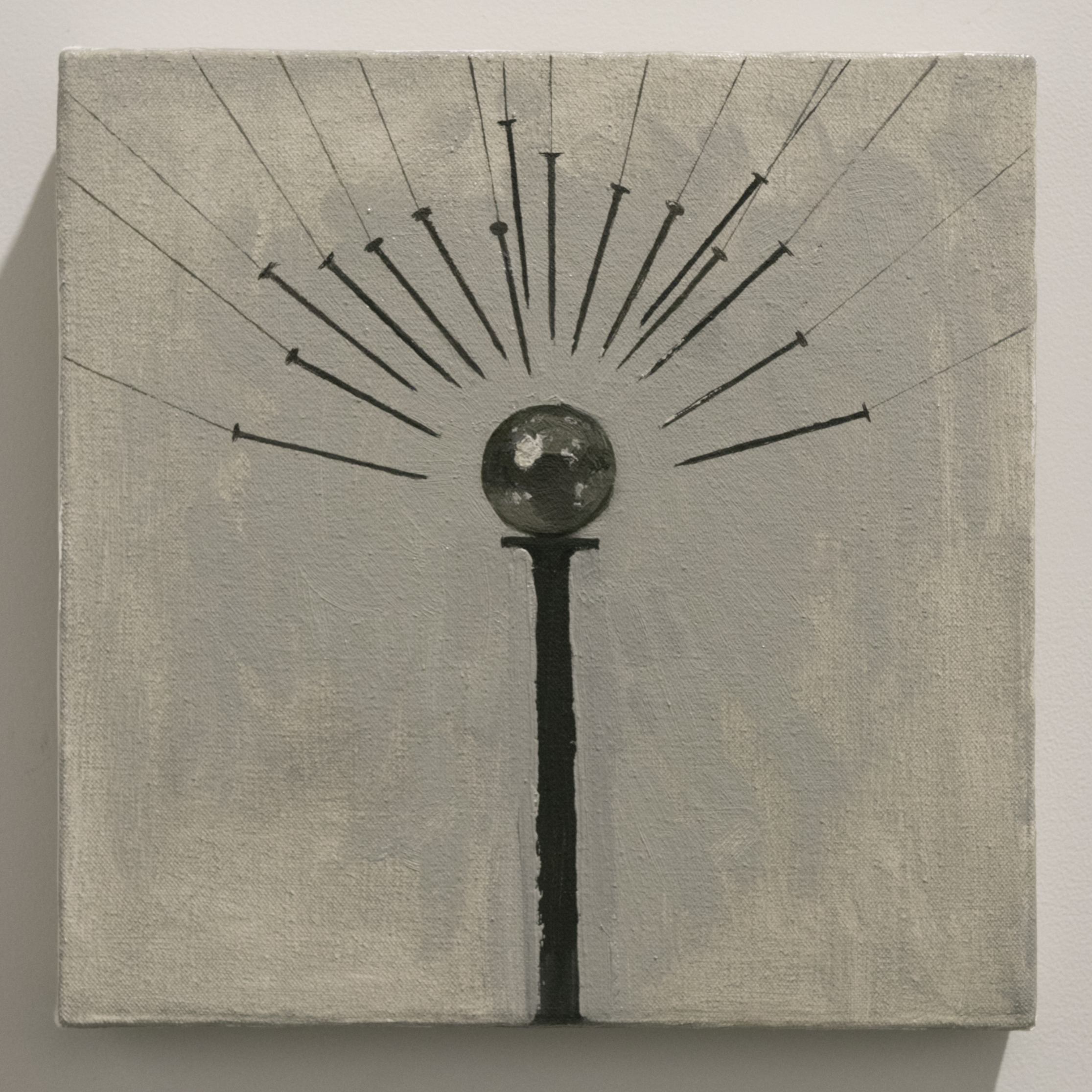

Haha yes, he has a self-portrait where he’s looking seriously out from the foreground and there’s a skeleton playing the fiddle and it’s titled Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle. The symbolism is so in your face and naive. You’d think that the sophisticated artist would think that’s a little too obvious. But that is what is so magical about it. It defies allegorical interpretation in a Sontagian sense. There is something so literal about it, that it doesn’t detract from a more intuitive significance. It was a whole new angle for me. When I think about symbolism, and how it is complicated and I might have to do a lot of research and understand the conventions of the time to get the true message, this is so direct and visual in a way which was refreshing and charming to me. It freed me up seeing this, when I had ideas and would think, ‘this is a little too obvious’, to just try it out and see if it worked.

You touched on the natural looking scenes. Then you have the pendulums and the magnet. It’s easy to relate your ideas to the landscapes but how does it relate to these works?

I had this idea of the confusion that comes with the scientific revolution, especially when you look at history and see the way artists and poets respond. They’re almost always coming from a spiritual place. As the scientific revolution happened and concepts of spirituality and religion were, not diminished but changed, people’s responses also changed. There was this part of me that wanted to bring that in and was wondering if the scientific and spiritual could be reconciled. The thing that appealed to me about those motifs was not necessarily the scientific aspect of it, although that was fascinating as well, but the visual, formal characteristics of those motifs – the simplicity of their form, the rhythm of it. So in a weird way I’m reading spiritual things into this more scientific thing. I liked how having this idea of kinetic energy and magnetic forces gives another thing to the other works where you might start to think about kinetic gravitational forces. The cosmic force of gravity pulling all these molecules in space. I thought it expands the readings of the other paintings that otherwise wouldn’t exist in a show of just landscapes.

釘と磁石—Magnet, oil on stretched canvas, 255x255mm, 2023

There is definitely movement in the other works, especially in the fabric pieces. Was that part of your considerations when painting? Wanting to capture this energy?

There’s a different kind of rhythm and pace to each motif. The swing of a pendulum is relative to our heartbeat, and the weight of a nail has some link to the proportions of our hands. It’s a one-to-one scale with the body and it’s very light and fast paced – a kind of human rhythm. Whereas the sea stack is slower. The way those rocks are formed you’d have a chunk of land, and the tide would come in over hundreds and hundreds of years, slowly eroding the land around it. On a similar scale, an erratic rock may be native to the peak of a distant mountain, but found in a glacial till at the bottom of a valley where it travelled to over the course of many centuries. I was thinking about these different kinds of rhythms and how everything is constantly changing but at different paces. Though we have a better intuition for the phenomena closer to our relative scale and way of life. The angle of a piece of fabric caught in the wind is maybe determined by the shifts in horizontal air pressure, but the diameter and weight are usually in relation to the human body, so perhaps its impression is somewhere in between. I like going through photos in NASA’s photographic archives and seeing planets, and the way light falls on them from a distant sun is just the way light would fall on a little ping pong ball. Even though the scale is so different the physics apply in the same way. I read a kind of poetics into that.

I guess something might have that feeling in the scale of things in real life. It’s the reason people go hiking on top of mountains, for this sense of awe and being within something powerful.

Like the way the light falls onto a mountain – you understand the way the shadows are cast are just that of a child’s toy, but suddenly you’re the little thing inside it.