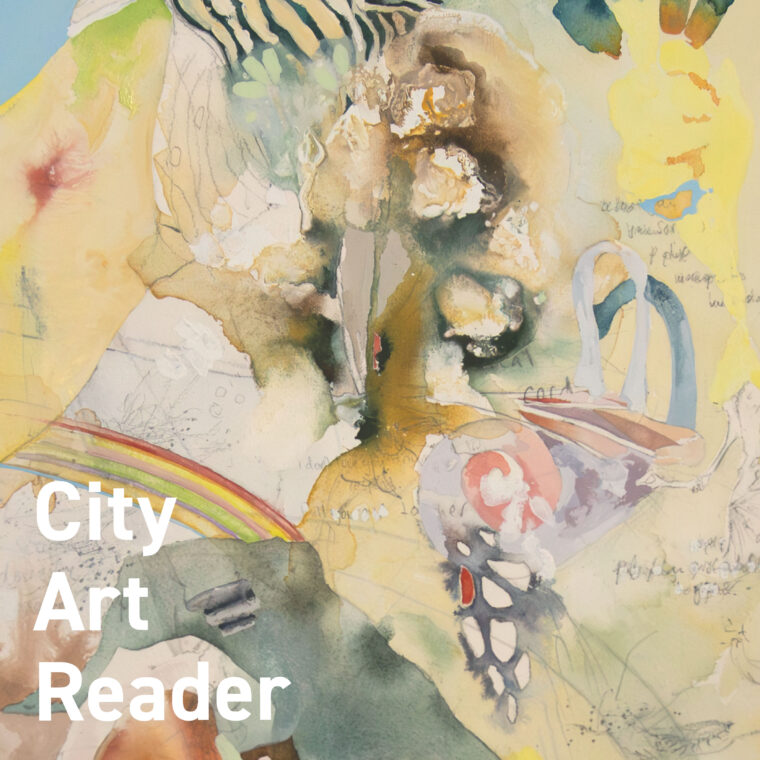

In Asphalt Panic Ōtautahi Christchurch based artist Rupert Travis investigates the area between work and play or dreams and reality. The works are inspired by Travis’ personal memories of growing up in Ōtautahi, intertwined with his childhood daydreams while in the classroom. Ahead of the exhibition, he discussed his works with City Art Depot gallery manager Cameron Ralston. Asphalt Panic opens 5.30pm Tuesday 20 June and runs through to 10 July.

Diabolo, oil on canvas, 735x865mm, 2023

Diabolo, oil on canvas, 735x865mm, 2023

Cameron Ralston :The thing that strikes me about your artwork, and a lot of work I’ve been seeing around lately, is this focus on childhood or adolescence. I’m interested to know where you’re coming from with that topic. Is it an attachment to a free-thinking imagination?

Rupert Travis: I’ve always found this interesting. When I was in Australia I was doing a bit of writing and there’d always be this child figure, or coming-of-age, in the way of a personal breakthrough. I’ve often thought about what is the interest there. I think what’s interesting is, as you slowly get older, you don’t know what the future holds, so that idea of looking at older people is incredibly alien. But every single person has been a child. It’s probably the most fun time you’ll have, because not only is everything provided for you but also every single year you look in the mirror, you’re a different person. When you get older, the last five years can become a bit of a blur – you can’t define them so strongly.

So, for the most part, it is about childhood, especially when you’re talking about dreams and how it is more fantastical and imaginative. You don’t have a fully developed concept of reality and your visions can be as wild as anything because you haven’t discovered the thing you want to pursue. The ignorance of children makes their world seem very fascinating and they have that amazing ability to dream. People always say the best thing you can do in life is never lose that wonder you had as a child. That intrigue about the most mundane things, like seeing a funny shaped piece of metal on the ground and not walking past it but acknowledging it.

Do these works take on child-like views of the world?

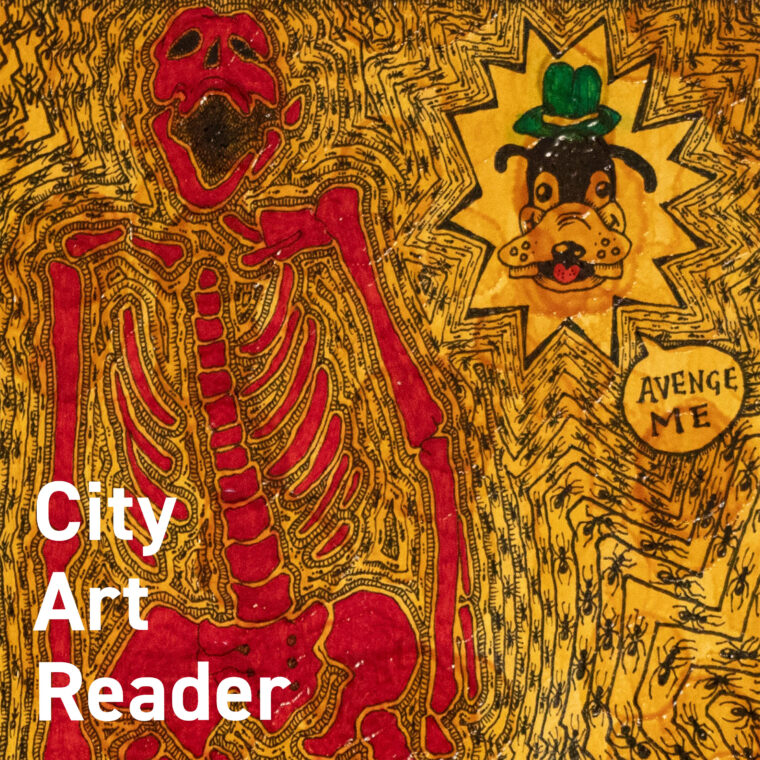

They jump between two different worlds, a merger of fantasy and reality. For instance, the idea of possums is fantasy, no one sees them that much, you might hear them at night but they’re a kind of dreamy animal that when you’re confronted with them they appear sort of like a demon with red eyes, kind of a scary thing.

Possum, oil on linen, 330x275mm, 2023

Possum, oil on linen, 330x275mm, 2023

I suppose as a child those feelings would be heightened too. But now looking at your works, they have a kind of contemplativeness, or calmness, to them. In the soft way they’re painted and stillness of the subject matter.

To be honest, and I think this is something that runs through my work now, it’s calm and it’s contemplative but it’s eerie, not necessarily a friendly conversation that’s happening. Often the figures are alone. This series is off the shoulders of something I was doing before starting uni, scenes of suburbia mixed with the sketchy escapisms. So things like hanging above the crocodile, it’s the escape of the mind – that allowance to dream. To get back to your question before, they’re kind of calm scenes, not rushed messy scenes, with a muted contrast which helps them to become a kind of faded imprint. But at the same time I think part of the quietness is a loneliness. Escaping to your own world.

The figures are quite anonymous and faceless – are you hoping people will implant themselves or are they depictions of you?

I think this goes for everything, they have this common element of lack of detail. As soon as you put eyes on a figure it no longer becomes a vehicle – I’m not a very spiritual person – but the soul lives within the eyes, whereas when you remove that it objectifies the figure and it becomes a form people can implant themselves into. Emmanuel Kant talked about using the dualities of faculties which is supposedly where we get joy. So if you paint something too obvious it becomes boring because you instantly understand it. Whereas if you create something with ambiguity your mind has to work harder to decode the picture. I wanted to treat the figures almost formally, looking at what determines the figure to be a figure.

I suppose the same thing goes with the animals which sit within the same ambiguous space?

Yes, and it ties in with the contrasts. It’s a balance to get it right, but I really didn’t want to use sharp contrast because it’s effectively a way to get instant recognition – heavily outlining something or creating a foreground-background contrast where the forms jump out at you. Whereas blurring the line where it cuts off and starts, you’re required to move away and into the painting. I quite like the idea of an artwork having two faces – the intimate face when you get up close and see the brush strokes and materiality, and the other side when you stand back and take in the picture as a whole. I think it’s especially complicated when you’re doing figurative work. When you do abstract art it’s often devoid of narrative, you don’t have to tell the story behind it as it’s happening within the work. But as soon as you put a human form in it people will immediately start to question what the points of meaning are, for instance why does she have a banana in her hand? I think there’s something quite nice about not giving everything away. Edward Hopper refused to ever talk about his work because he claimed he didn’t have any idea about what he was doing. But when you look at his catalogue of work as a whole, he’s incredibly identifiable as an artist in what he was trying to do with narrative. Rodeo, oil on canvas, 535x635mm, 2023

Rodeo, oil on canvas, 535x635mm, 2023

Do these works tie into your recently completed masters studies at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts?

Previously I’d done human figurative scenes, then for my masters I removed the figures to see what it did to the picture. Talking again about the empty forms or vehicles for the viewer to implant themselves, I wanted to remove the figure altogether and investigate if you still implant yourself into the work, or do structures become personified? With this exhibition I wanted to slip back into using figures. All my works throughout my studies played with dreamscapes in a sense colouristically. But with this I wanted to have fun with it on a new level. Going almost naive or childlike in the approach. All my university works ended up quite serious because they had to be. Whereas in the real world you can be more playful.

I think finding it tricky to settle on what a complete artwork is to you is a common feeling, especially coming out of an academic institution.

There’s always that fun question of when an artwork is finished. What I find funny is when I first start doing the undercoats of a work, everyone says stop and seems to like it. But then I think, part of that is when I start a work, I use strong contrasts, trying to make it clear where everything is, and then I slowly build it up. This creates a sharper image, possibly allowing an instant understanding of the work. However, there is actually less intimate detail upon closer inspection.

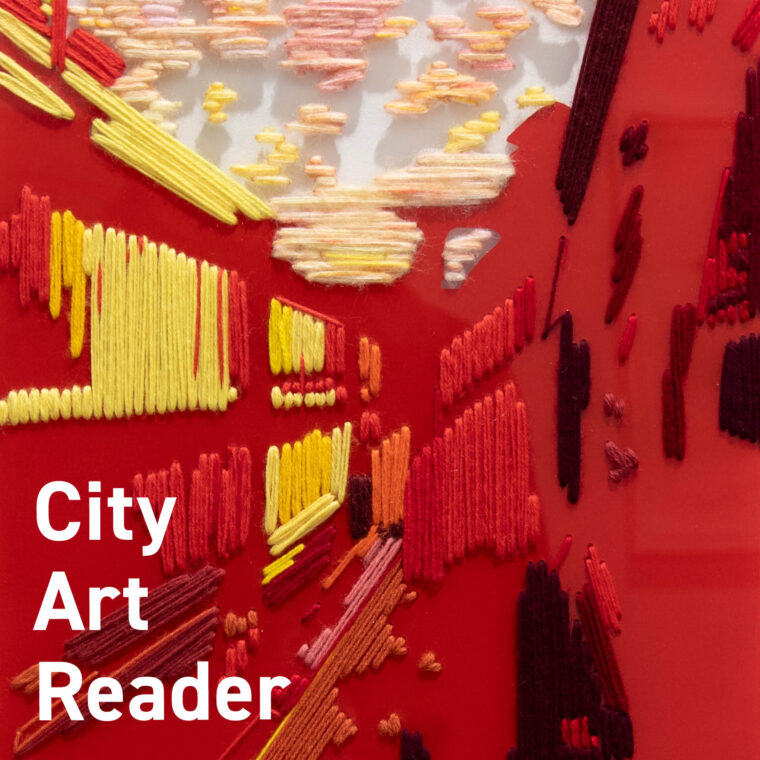

Tell me about the mediums you used in the pieces to obtain this look.

All the works are oil on canvas or linen. Not heavily gessoed because I find there’s something really interesting with some of the pigment being absorbed by the pigment underneath, so you get this almost dyed effect in place. I had quite a lot of fun with getting certain applications of paint. Colouristically, there’s obviously a running theme of pink and warm tones throughout them.

What does Asphalt Panic refer to?

The name references lunchtime at school. I have a nine-year-old niece, and it’s hilarious hearing her talk about the scandals and politics that are happening at primary school. When you consider it retrospectively as an adult you realise how ridiculous much of that stuff is, but it’s nonetheless real at the time. A lot of my time at school and after school was spent on the asphalt. I think panic is a fun concept too. Things like anxiety get too real and too heavy. Whereas panic is a short burst of feeling, almost rushed or hurried.

Lagoon, oil on canvas, 430x360mm, 2023

Lagoon, oil on canvas, 430x360mm, 2023

The characters in the scenes don’t seem too panicked by their situations. Except for maybe the character in Lagoon.

Ha ha yeah, they’re quite calm. When you see the body of work it’s almost like a parallax of different lives lived at once. So, in the least cliched romantic way, you as the viewer become the person on the asphalt panicked looking at all these options, thinking of it like a fork in the road.

I see there’s elements of fantasising as a child about what your life could be. Those thoughts must come from what you have been exposed to. Did you have experiences of, for instance, the circus as a child?

One of my favourite memories is going to Cirque du Soleil. Again, this comes back to seeing my niece as an adult, how influenced you are by what you should think. So, I don’t know about you, but it’s relatively common for a kid to think about running away to the circus. It’s almost this trope of what a kid should dream of doing. But a lot of people have no idea what that would involve, yet a lot of them will have that fantasy of dumbo, trains and carriages and living this exotic gypsy life. Whereas it’s very different, business-like now. I don’t think the name is about the anxiety of where you will go or that dichotomy of the adult and child fighting. It’s more a play on remembering the ridiculousness of childhood and how every child panics, but every panic is short-lived. Almost like little tantrums. You take the figure swinging above the crocodile from a tree branch, it’s a made-up scene of unrealistic momentary panic.

Through The Hoop, oil on linen, 405x350mm, 2023

Through The Hoop, oil on linen, 405x350mm, 2023

In contrast to your recent master’s exhibition, these works have more of a sense of fun or humour. Is that something that you would characterise your works by?

They’re more ‘doodled’ and some are definitely more humorous than others. My university works were very refined. Perhaps that’s the wrong word but they felt very edited, which can be really good but can also lead to losing a bit of the self in the works. Picasso famously talked about how it took him four years to paint like Raphael and a lifetime to paint like a child. It’s that notion of being so engaged with your idea and not putting too much intellectual thought into your work. I’ve got this strong view that if you just paint you will innately come out with an idea. A lot of what we’re drawn to, even if it’s made up or observational, comes from some sort of innate subconscious. When you’re editing, you’re paying a lot of attention to what’s going on around you and what’s influencing you, that it might go far away from the initial idea. I think there’s something valuable in keeping it less edited and more fun. I was just having this conversation with Lucia Sidonio, about when to leave a painting. It’s about finding that happy medium between over and under working something. I probably played with Rodeo the most, though it perhaps looks the least like it. One of the things I wanted to do with it was not bring the back horse up too much and leave things less defined. I think I enjoyed that this series ended up being sketchier, or again, doodled.

Did you do research into dreams? Did these works come from sketches or doodles?

I didn’t research dreams. I was actually doing animation years ago before university. I was doing very sketchy paintings at the same time. I’ve always kept them and wanted to do a series of paintings based on them. I always wondered what they would look like if they were worked on or rendered more, so this is where a lot of this series came from, rather than starting to investigate a research topic. It’s a mix of that initial sketching idea, movies I watched growing up – films like Albert Lamorisse’s White Mane which looked at dreamscapes – and then the reality of things, like the possum.