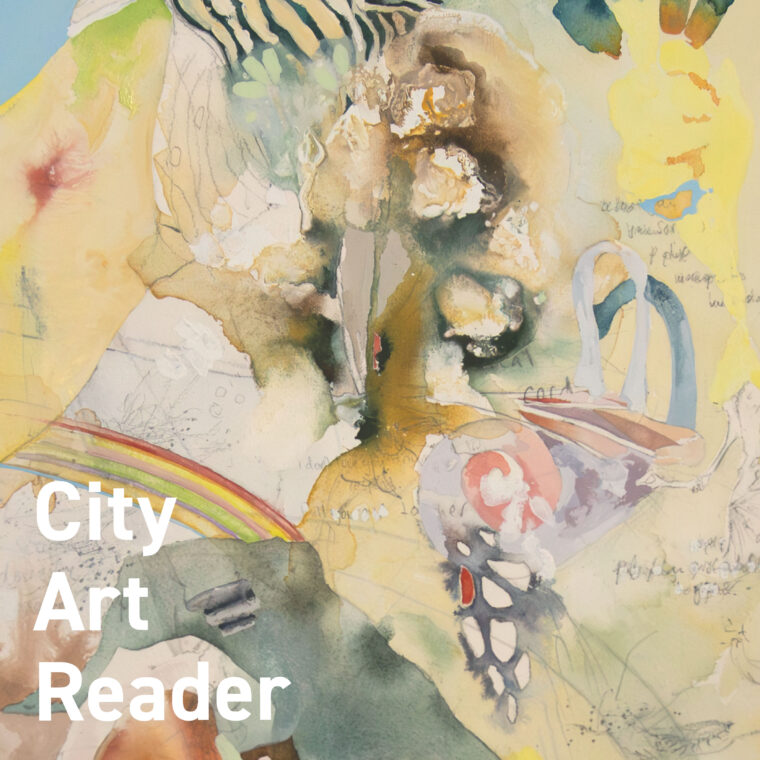

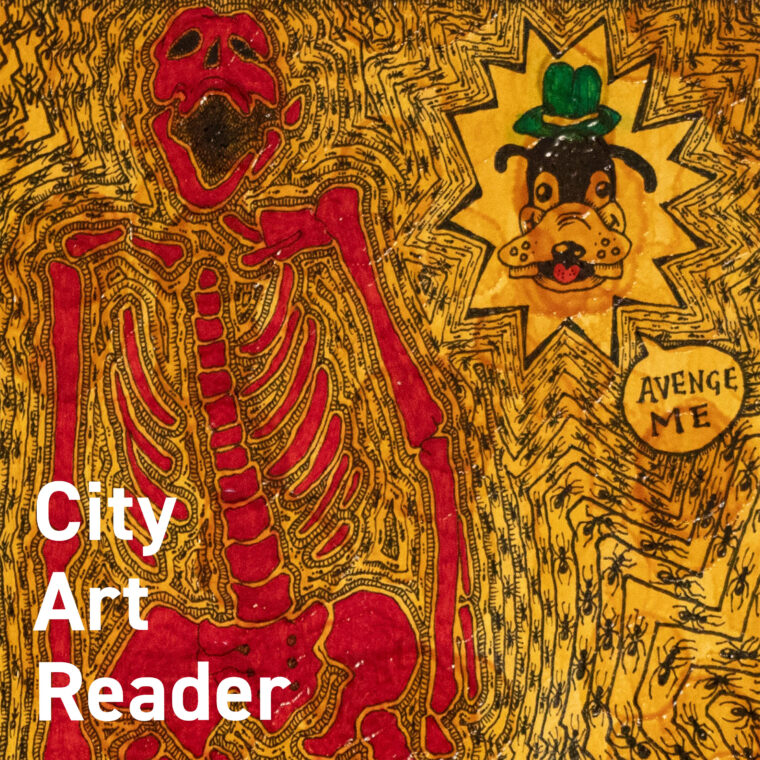

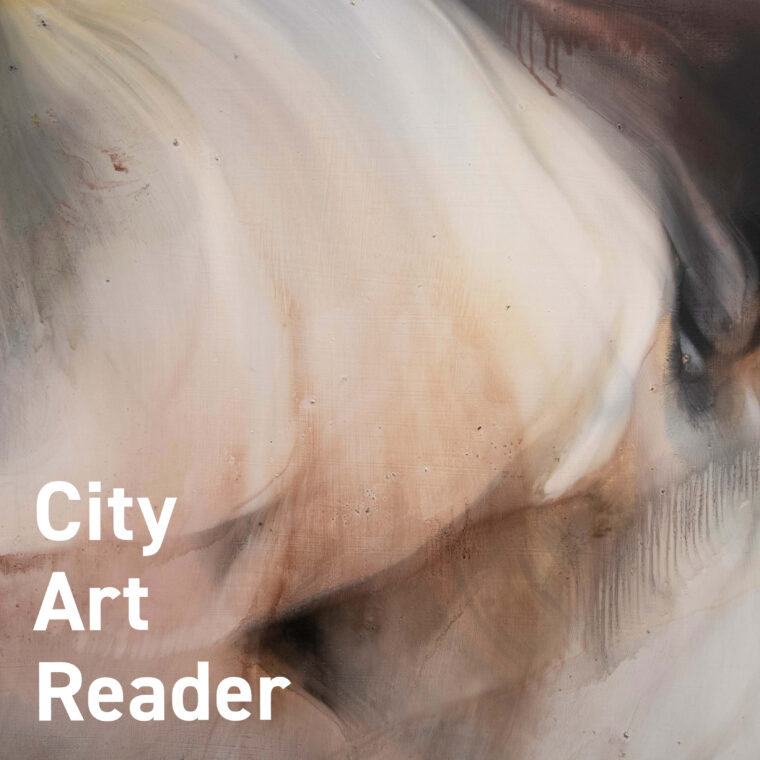

Tahlia King (Kai Tahu and Ngāti Maniapoto) is an Ōtautahi Christchurch based artist whose work uses textiles woven through acrylic to plot out her abstractions. In her new body of work Red Sky Warnings she depicts interior and exterior scenes in a red palette which speak to the unpredictable nature of life on the near horizon. Red Sky Warnings opens 5.30-7pm on the 9th of September and runs through to the 29th of September. Ahead of this King spoke to City Art Reader editor Cameron Ralston about her show.

Red Sky Warning, acrylic perspex, wool, yarn, silk mohair, paint, 395x800mm, 2025

Cameron Ralston: What’s this body of work about?

Tahlia King: These artworks are about the emotional experience of facing a crisis. Being confronted by a kind of inescapable warning that meets you, which you can’t really get away from. You start to realise that the things around you that feel solid, safe and foundational are quite fragile. That’s where the works came from.

How is that reflected in the work? Is that coming through your choice of imagery? You’ve depicted structures or homes.

Originally the concept came from the colour red and then that moved to the old saying about the ‘Red sky at night, sailors delight. Red sky in the morning, sailors warning’. I had started off trying to make photos that replicated old burnt-out photos from the 70s and 80s that have that ruddy orange fading over time. I made my own like cellophane filter for my camera and started taking images of things around me and my direct environment – backyards and fences, things like that that are just our everyday staple environment. The places that we know the best. Homes and houses that we’re all very familiar with.

Is there something in the translation and abstraction from a photograph to what you present here? What is it about the weaving on the acrylic that ties it into those messages in the work?

I try and make works about our contemporary lives and our current experience. We’ve got quite strong emotional connections to both materials – the plastic and the wool. They’re polar opposites as far as the way it makes us feel. Plastic is very much a part of our current lives and will remain so. It’s something that we don’t really like very much. It’s a sign of how industrial and manufactured the world has become. That’s contrasted against the soft comfort of the wool. It’s something that is usually very soft and fragile itself. In anchoring the textile down to a very industrial material that we have strong negative or conflicting feelings about, it’s kind of that mesh of the way things are in life at the moment. We have this balance of looking for comfort and homeliness set against the reality of our quite industrial contemporary lives.

Your work plays with those balances. The balance of the two different materials. The balance of figurative and abstract. You talk about the red sky warning, there’s also a balance in that saying don’t you think? It’s not purely ominous – although these works perhaps have that feeling.

The thing that stood out to me about that saying is exactly what you said. In the morning it’s an omen, but 12 hours later this same sign is that you’ve passed the storm. It’s all behind you. You’ve managed to overcome things. So, I intentionally made them ride that line of you don’t know what time of day it is, you don’t know if you’re dealing with the sunset or the sunrise. It’s the same sign that can show you it’s time to face it, but you also could have passed through the worst of it. And that there’s still a hope there, even though it’s a really unmissable final warning.

Is that speaking to personal experience?

Yeah. Anything from just growing up in Christchurch and living here through the earthquakes and experiencing the reality that things can change very quickly. Even in things that you feel are strong and safe around you. It’s a universal experience that happens to people throughout life. You’ll be met with an unexpected thing that comes out of the blue. You wake up and it feels like a crisis has suddenly just hit your back step. And then you just have to go with it. It’s not one of the nicest universal experiences that we all go through, but we all have these moments where we must deal with what’s happening around us.

In the face of all that, do you see these works as comforting?

Yes and no. While they are comforting in the textiles and even some of the brighter colour palettes which would normally speak to happier things, I wanted to pull it back. The life around us and things that we experience are beautiful, but there’s an edge to it that they can be lost. They can be damaged or scary. So that was sort of the balance of comfort and harsh reality.

On Eastern Winds, acrylic perspex, wool, yarn, 395x800mm, 2025

I’m interested in the process of making these. There’s several choices that you’re making around thread location, direction, colour and so on. Does all of this emerge through a planning process?

It’s very process driven. There’s a lot of stages that go into it. The photos are my first stage of abstraction and in every stage I move through such as the drawing and then converting it to line is abstracting it again. I need to know exactly what it’s going to look like before I even start stitching, because each of them has hundreds of drill holes that have to be put in first. It means it’s a very long process to make each of them.

It goes through phases where the plastic goes from being a solid thing to becoming more fragile because I’ve perforated it so many times. Then the stitches come back in and almost shore it up again and give it back its strength. But there’s no rushing it once it gets to that point, every drill hole has to be done, every stitch has to be done. It becomes quite a long process of each stage to get to the final work.

Have you always done like weaving?

In different ways over the years, for sure. So, when I was younger at kapa haka learning those kind of skills through mahi toi and toi Māori. My mum has always been a knitter and a sewer too. I think of it as I’m a maker, you know, I make things and it’s a very hands on, physical kind of process.

Do you see the works having a connection to whakapapa or your identity? Or is that something that you hold separate from your making?

Yeah, I try and keep it separate. Not intentionally necessarily, but just because I’m trying to deal with universal experiences or emotions. That’s why it’s I use motifs like houses and things that everyone is familiar with – the weatherboard house, backyard and porch. It expands it beyond my experience of things and my heritage to hopefully things that everyone can relate to.

So, these are Ōtautahi Christchurch scenes?

Yeah, I do try to make all my works focused on a very local perspective. Just taking images and photographs in my surroundings or in Christchurch as a whole, and then hopefully it can speak to Aotearoa New Zealand as a wider view. Even just the skyline is something that’s so dominant in Christchurch. No matter where you are, it’s a feature of the city. But hopefully it doesn’t matter where you’re from or who you are, things like a house and a backyard can hit a familiar feeling.

You recently completed your Master of Creative Practice at Ara. Do these works have a connection to your study and thesis?

My masters work looked at the cost-of-living crisis in New Zealand and our experience of it in Christchurch specifically and the places that we confront financial stress here.

So, where this work carries on from that is in moving to a wider lens of crisis in general, rather than a specific experience. There’s a lot of different areas in contemporary life where you run into a crisis of some kind. It is something that we have to confront. My thesis was around the emotional experience of things and how to use abstraction to carry narrative and make emotional connections through line, colour and stitch. That is the basis of what this new body of work sort of carries on from.

Are there artists who have had an influence on your art?

The artists who have influenced me the most are artists like Edward Hopper and Ed Ruscha, whose works look at the changing experience of modern life and the impact that it has on us as a society. Locally, the artist Buster Black, whose work depicted the Auckland suburban landscape at night, helped me to narrow my focus on to our direct environment and our daily experiences of the places where we live, and then groups like the Mataaho Collective inspire me through their use of industrial materials, textiles and intricate processes to comment on the sociopolitical issues that we face in contemporary life.

Watching the Weather, acrylic perspex, wool, yarn, silk mohair, paint, 800x400mm, 2025

How does the see-through quality of the acrylic play into the artworks for you?

It’s one of the reasons I first started working with plastic, because it gave me depth, light, reflection and negative space. These woollen forms are then floating in space and even though the works are essentially flat they get a dimension. I consider all angles of viewing the works.

It means that I can take something that’s a flat form like a line and kind of push it into a three-dimensional area. Even just being able to paint on the back and front of it means I’m working with depth in a way that I couldn’t without the plastic.

Your work has a very tactile quality, which forms part of the attraction to them.

Yeah, I hope to try and make it feel like you want to touch them and get up close and engage with them.

Is there something that you’re hoping the works will evoke when people look at them?

I hope the main take away would be something about the understanding that we get confronted by challenging things and it can be very scary and ominous, even frightening to face these things. But the reasons that you’re doing it are still there. You know the homes and what you value in your life are actually fragile, but you can overcome that – like that saying, 12 hours later the same red sky means that you’ve made it through. What seems scary in the morning, at night time can just be like a beautiful sunset. So that’s hopefully what it feels like.