For eight decades the work of Colin McCahon has loomed ever larger on our cultural landscape, fuelling wonder, outrage, praise, discomfort and a kind of mystified awe. This year is his year. Marking 100 years since his birth on 1 August 1919, already we have seen a rush of exhibitions, events and talks acknowledging the importance and indisputable impact of an artist who, perhaps comparable to Janet Frame in the literary world, carved out a singular but persistent New Zealand modernist vision.

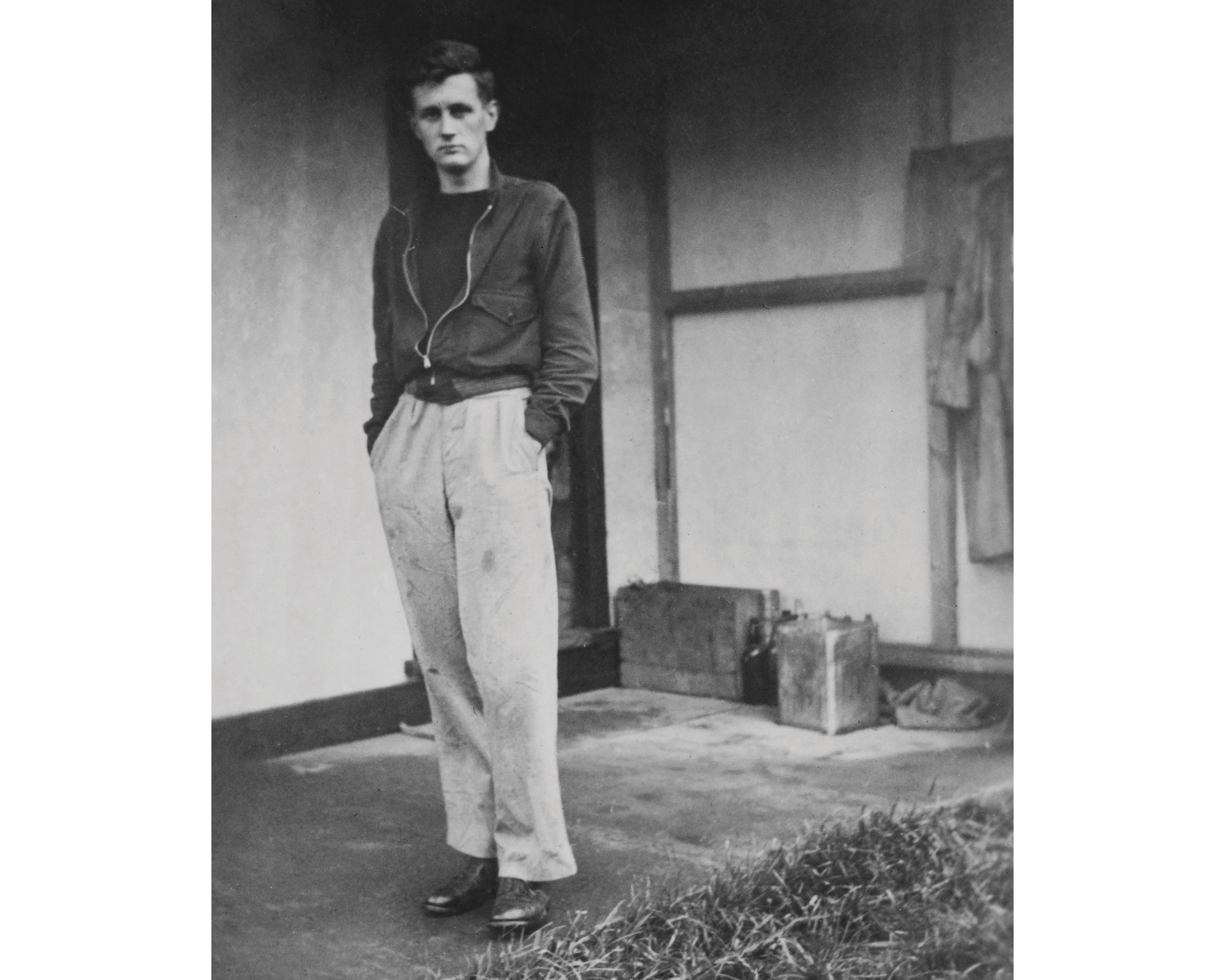

Colin McCahon at Pangatotara, 1939, photographer unknown

Colin McCahon at Pangatotara, 1939, photographer unknown

The first book off the rank is Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction. Vol.1 1919–1959by former associate professor of English at the University of Auckland, Peter Simpson. Simpson came to McCahon’s work as a specialist in New Zealand poetry. He ran a university course called “McCahon and the Poets” and has researched and written about the artist through much of his career, including his 2007 book, Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years, 1953–1959, and Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933–1953 (2016). Here, in a hefty 325-page volume, he embarks on an overview of the artist’s entire output, to be completed next year in the publication of volume two, Is This the Promised Land? covering McCahon’s art practice from 1959 until his death in 1987.

This first volume is comprehensive, extensively researched and features superb reproductions of McCahon’s paintings. The title, There is Only One Direction, is taken from a painting of Mary and Jesus gifted by the artist to James K. and Jacqueline Baxter in 1952. One of his last figurative biblical paintings, its pared back depiction of the downcast mother and her solemn adolescent son is redolent of quiet foreknowledge of Christ’s death. But the words of the title also appear in a number of works quoting lines from poet Peter Hooper: “Poetry / isn’t in my words / it’s in the direction / I’m pointing”. They appear again in McCahon’s own stated sense of purpose as an artist: “There is only one direction,” he wrote in 1971, “and this should be apparent in the painter’s work.”

Colin McCahon, ‘There is only one direction’, 1952, oil on hardboard, 692 x 550 mm

Colin McCahon, ‘There is only one direction’, 1952, oil on hardboard, 692 x 550 mm

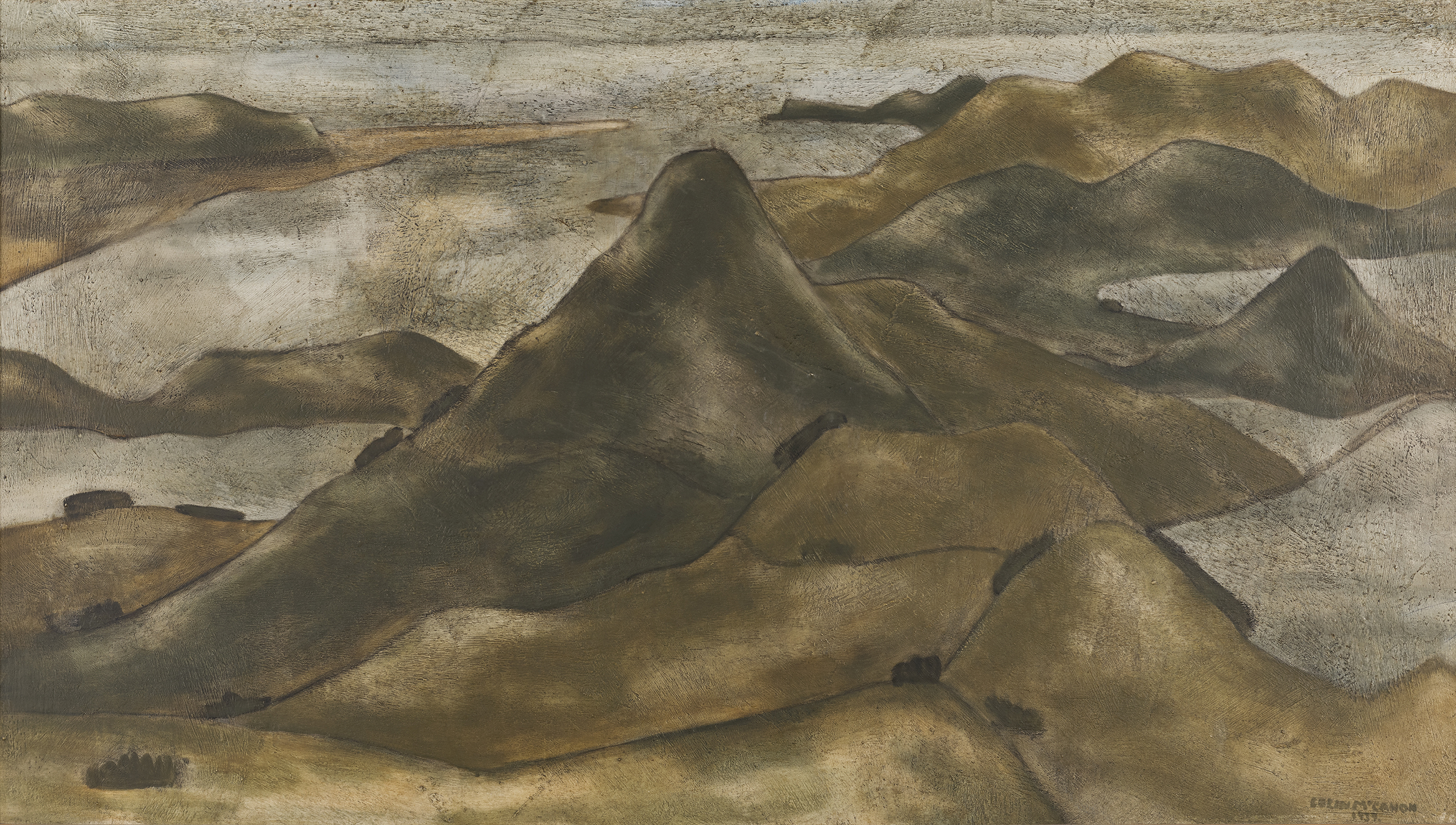

Simpson works diligently through a rich archive of letters, exhibition catalogues and reviews to identify this direction. It is a chronological examination undertaken with academic gravitas as he follows the artist and his growing family up through the country, from the brooding hillscapes of Otago to the golden light of Takaka’s hills and the stagey appearance of Madonnas and angels, back down to the ordered plains of Canterbury and up to the shattered mosaics of colour and light in the Waitakeres.

Colin McCahon, ‘The Valley of Dry Bones’, 1947, oil on canvas, 885 x 868 mm

Colin McCahon, ‘The Valley of Dry Bones’, 1947, oil on canvas, 885 x 868 mm

At every place and at every turn, at every pitch between realism and abstraction, figuration and word or number, Simpson identifies a consistant conflation of landscape, art and religious faith or doubt. As he writes, landscape for McCahon “was never merely a matter of hills, plains, horizons, skies, clouds, trees and water… Right from the start other things were going on.”

This is supported by McCahon’s own comments – luckily for Simpson, the artist was a prodigous letter writer. When his first “masterpiece”, Harbour Cone from Peggy’s Hill (1939), was rejected by the Otago Art Society, McCahon told fellow artist and long-term supporter Toss Woollaston, “I imagined people looking at it then looking at a landscape& for once really seeing it & being happier for it & then believing in God & the brotherhood of men & the futility of war & the impossibily of people owning & having more right to a piece of air than anyone else.”

Colin McCahon, ‘Harbour Cone from Peggy’s Hill’, 1939, oil on hardboard, 750 x 1333 mm

Colin McCahon, ‘Harbour Cone from Peggy’s Hill’, 1939, oil on hardboard, 750 x 1333 mm

If this is a biography, Simpson writes, it is a biography of a career, “not the man.” McCahon’s wife Anne Hamblett, a highly accomplished artist in her own right, is a faint presence in the book, as are their children. Nor is there much attention to his stage design work or his painted glass. Rather, it is a methodical painting-by-painting account of McCahon’s most important works. The pace is measured, the tone instructive rather than impassioned – Simpson’s own caught breath is difficult to gauge. But through the many letters and the art works themselves Simpson cannot help but give colour to an artist raised, as McCahon wrote, in a “gallery-going family”, imbued with a strong protestant work ethic, driven by an anxious faith, a love of poetry, of books, of art. Simpson is at his best when identifying McCahon’s influences, revealing him as a reading, observing, intelligent artist finding inspiration in art, landscape, “high” and popular culture: the handwritten signs at the local tobacconist, the speech bubbles of a Rinso ad, a Phaidon book on Titian, the white cross on a North Otago hill marking the spot where a parachutist died, the sight of linesmen on ladders in Māpua installing power poles – the equivalent to a crucifixion, he wrote – and his “career-changing” trip to the United States in 1958.

Colin McCahon, ‘Cross’, 1959, enamel (‘Solpah’) on hardboard, 1219 x 762 mm

Colin McCahon, ‘Cross’, 1959, enamel (‘Solpah’) on hardboard, 1219 x 762 mm

There will be more to come. Justin Paton’s McCahon Country is due out next month and Wystan Curnow’s book on the artist is expected next year. One step ahead of these, There is Only One Direction sets an authoritative benchmark for McCahon’s centenary year.

Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction. Vol.1 1919–1959 by Peter Simpson (Auckland University Press, $75) is due out on 3 October.

All images courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.